The Missing Spark of Decision-Making in Design

The following essay tries to discover how decisions are made within a design process. They can’t be made by means of analysis and logic. This is due to the specific type of problems that design has to deal with. These so-called ill-defined problems are ambiguous and not well-defined. Decisions in design processes happen constantly, but on an abstract level between divergent and convergent modes of thinking. To bridge this transition there is a powerful tool in design called synthesis. A designer using synthesis is able to grasp multiple, incongruent, competing ideas and manipulate them at once and in parallel into something new.

Intro: The decision dilemma

Imagine this situation: You are a student getting the assignment to develop a new concept for a future solar car. After research you have gained numerous data on solar cars and future mobility. How to go on? And how to decide which is the best direction?

To approach an answer you have to step outward and analyze the assignment in the first place. First of all, if we talk about a decision we try to solve a problem, because as Simon (1990) examined, problem-solving is ultimately a process of decision-making.

The conception of a future solar car is not a well-defined problem and can’t be analyzed in a scientific manner. As Lester and Piore (2006) stated analytical processes work best when alternative outcomes are well understood, clearly defined and distinguished from one another. In the solar car example the alternative outcomes are neither well understood nor can be distinguished from one another. Rather the problem can be determined as so-called „ill-defined“ or „wicked“ according to Buchanan (1990), because it can’t be solved by the means of pure logic or analysis. Especially designers are used to deal with this type of problems.

Outline: Define the spark

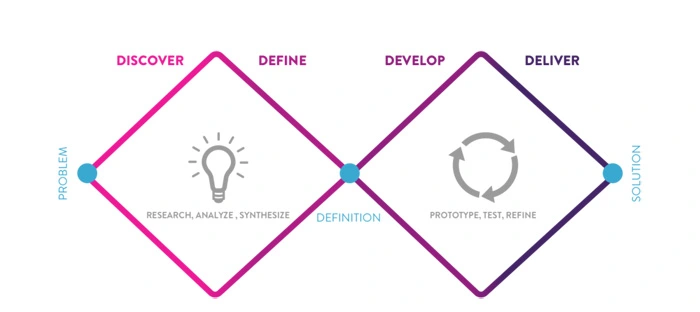

If you dig deeper into the situation at the outset of the text you are at the end of a certain stage (e.g. research) and at the beginning of another stage (e.g. ideation). On an abstract level it is more a point where you jump from one mode (gaining lots of data) to another (focusing on specific data). These two modes are described in Lindberg (2010) as divergent and convergent modes. The divergent mode opens the space to find as many alternatives as possible, whereas the convergent mode the condense the gained data (many alternatives) by selection and variation. On a time level it could last from a few moments to several days depending on the amount of data and the overall time constraints of the project itself.

Typically, for an inexperienced design student the question arises how to go on with the design process in this undefined vacuum between divergent and convergent design modes. This vacuum is usually characterized by a feeling of uncertainty during this phase the design student feels lost and disorientated. There is intuitively a wish for a quick solution to go on with the process bringing back the certainty that the student knows what he/she is doing. Unfortunately, this may lead to a single solution that cannot utilize the potential possibilities of insight that uncertainty can bring up (Self, 2012).

This uncertainty is naturally embraced by a designer. As a consequence a designer has the ability to hold up the tension in this moment of uncertainty. As Cross (1980) mentioned there are specific skills of a designer that empower her/him to bridge the gap between convergent and divergent modes finding the missing spark of decision. This gap can be defined as design synthesis.

Synthesis: The drug for a designer

A designer appears from the outside perspective somehow like a magician, because a designer’s activity appears effortless and immediate. According to Kolko (2011) this feels only that way, because the output is usually new and exciting. But the perception of intuitive decision-making is misleading. The trick behind the magic is that a designer uses the ability of synthesis. Kolko defines this ability as follows:

"It is the ability for the human mind to grasp multiple, often incongruent and even competing ideas and to manipulate them – at once, and in parallel – into something amazing. Synthesis allows for multiple hypotheses, ideas, themes, patterns, or trends to be mapped and diagrammed, and consumed and explored. It is a process of judging (...)" – Kolko, 2011

Synthesis is not simply there, but requires a constant evolution of ideas and the creation of form. It is a tool to move from gathered data (research phase) to specific design concepts (ideation and concept phase). The process of synthesis can last a few moments or several days depending on the complexity of the problem and the designer’s experience. The more experienced the designer, the faster the synthesis process, the more magical the output will appear to others. The ultimate goal of synthesis is individuality and diversity that brings up the innovative concepts and approaches. How this goal can be reached is explained in the next chapter.

Drive: Tools for safe(r) design decisions

In design you have to be aware that design decisions are rarely safe. As in most cases a designer has to deal with ill-defined problems there is a simple, but not easy strategy to solve such problems:

Due to the wickedness of the problem there is no analytical or scientific way to decide in such a case. This may be the reason that besides inductive and deductive reasoning there is a third form, especially used in design: abduction (Martin, 2009). Abductive reasoning means to adopt a hypothesis. These somehow „best-guess-leaps“ support you in broadening the solution space getting numerous design alternatives. Still there are some other drivers that help a designer to utilize the power of synthesis or in other words support the decision-making the design process.

Tool: Patterns

A pattern contributes to our ability to make decisions in a design process. A pattern identified in research acts as a guideline or a constraint to support further ideation phases.

Example: If you gather numerous data about the design problem (develop a future solar car), at first you will have no clue where to start. If you focus on patterns in the research data such as building analogies or analysis of automotive trends (e.g. retro style) you can develop first design alternatives.

Tool: Culture

To nurture synthesis there is a need for a specific design culture that consists of setting up constraints, working in a playful manner and visual thinking. Constraints can be adjusted as assignment rules by a client, but in most cases there are mere guidelines that support the designer to follow different directions. Playfulness describes the possibility to ideate in a crazy manner and play with different ideas. Visualization acts as a primary mechnism of thought. Sketching, building models and prototyping are essential means to find decisions in a design process.

Example: In the case of the future solar car concept there could be some fixed constraints (e.g. four wheels), but also other constraints that had to be found that define already the design concept to some degree (e.g. maximum surface for solar panels). Playfulness help you to broaden the constraints and play with them or find other constraints that were hidden so far. Visualization supports to clarify and evaluate ideas.

Tool: Flow

Csikzentmihalyi (1997) describes the flow as a state of full concentration with the activity at hand, in which peole are so involved that nothing else seems to matter. The designer in flow gets immediate feedback and knows if she/he is on the right track.

Example: A defined project room supports you as a designer to find the flow. All gathered data (visuals, ideas, concepts, models, …) come together in a room where no one can disturb the work in progress.

Tool: Experience

Experience is the reason why design looks sometimes like magic. It is the key for speed in the design process and quality in the design result.

Example: Experienced masters in a design team can guide you through the process and speed up the synthesis process to bridge the gap between design research and actual design doing.

Tool: Design tools

Supplementary, there is a broad range of design tools to support different phases or modes in the design process: Affinity diagramming, concept mapping, reframing, opportunity mind map, persona definition, etc. represent only a small selection of common tools.

Outro: The future

Even if there is a basic understanding of synthesis in design processes and how to utilize this power, there is still a mythical component that remains hidden. Research work about design processes and designer’s knowing and doing is still in its infancy. Maybe the reason lay in the analytical and scientific approach trying to understand the ill-defined problem of designing the future.

References:

Feedback

Back to top